I sometimes forget that I grew up on network television. As a kid, I tuned in at five p.m. for Power Rangers and watched Cartoon Network on cable whenever I was at my grandparents’ house. I remember watching “Mythbusters” with my dad and “Tom and Jerry” with my little brother. Network TV was the height of visual technology, and aside from DVDs, it was the most convenient way to entertain oneself. When network TV captivated the world, especially America, for forty-odd years, the sitcom genre reigned supreme. “M*A*S*H,” “Full House,” and “The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air” were household names. The sitcom era reached its apotheosis when “Seinfeld” emerged in 1998, making Jerry Seinfeld one of the wealthiest entertainers of all time and immortalizing the sitcom as a hallmark of entertainment in late-20th century America.

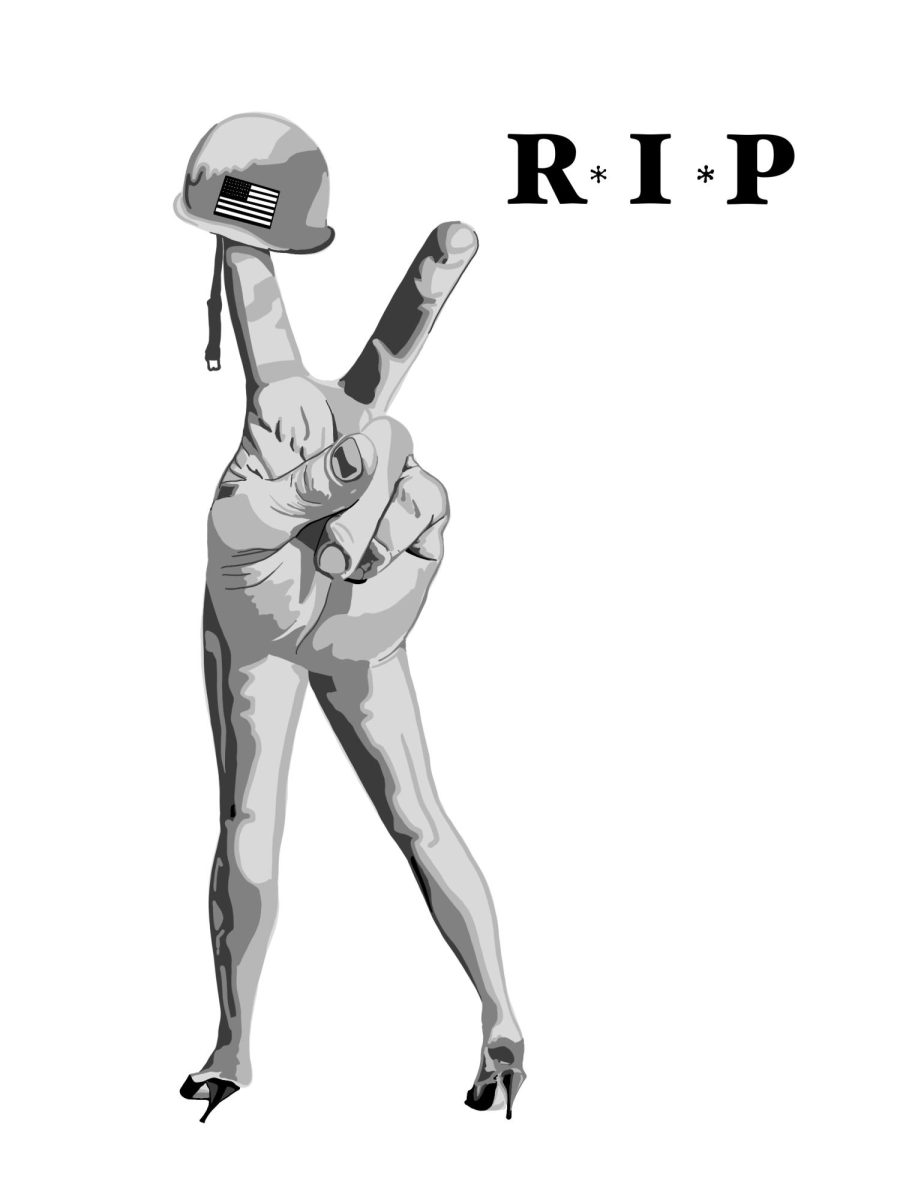

The sitcom, at least in its original form, is now dead. Gone are the days of laugh tracks, live studio audiences and self-contained episodic plots. Shows like Friends and The Big Bang Theory were perhaps the last of this kind, and some might blame the emergence of streaming. In an era of fast-grab entertainment with little delayed gratification, the traditional sitcom doesn’t cut it for modern audiences in its slow development and mellow pace. “Networks understood that not everything will be a hit right away and that shows need time to grow. Streaming services don’t care as they look for instant gratification and will even cancel shows that are already finished,” said Jamie Parker of CBR. Streaming services appear to have less and less faith in their projects, canceling even successful shows after one or two seasons. Are audiences losing interest this fast, or are streamers underestimating their audiences?

One can’t forget that sitcom popularity peaked during what might be called the “Golden Age” of America–between the Cold War and the war on terror. People were at peace, relatively unbothered by social issues. Sitcoms catered to that sense of public calm, allowing writers to create entertainment out of the mundane. The world has changed since then, and entertainment that attempts to simplify and romanticize American life does not carry the appeal it used to. The public is once again preoccupied with war internationally and social justice domestically, and our tastes in entertainment have changed to reflect that.

It seems the only way forward for the genre is what I might call the “postmodern sitcom.” This type of sitcom demonstrates self-awareness and frequently crosses stylistic boundaries. One might expect of this genre a more detailed overarching plot and a greater sense of social consciousness thematically. One great example of this is “WandaVision,” a superhero sitcom set in the Marvel Universe. Every episode is styled to emulate the sitcoms of a different decade, and the plot twists and turns until the show is no longer a sitcom but something else entirely.

Another example is “Community,” which begins as a reasonably generic sitcom set on a community college campus but later evolves into multiple realities and other outlandish plot devices. It is stylistically experimental, with one episode using claymation and another set almost entirely in an 8-bit video game. “Community” explores themes of racism, substance abuse and parental estrangement with greater sensitivity than is typical for the genre. The fourth wall is broken constantly. Sitcom creators have realized that the genre must be reappropriated to fit the tastes of modern viewers, which entails both social consciousness and self-consciousness.